WHN Admin.

Admire her as one does, and as impressed by the ideas she expresses in fiction, and the beauty of her prose, this quote from Virginia Woolf is a reminder of the value of women’s fight to achieve gender neutral language:

‘Every secret of a writer’s soul, every experience of his life, every quality of his mind, is written large in his works.’ Virginia Woolf

As is clear from the quote below, Virginia Woolf knew that ‘his’ did not cover ‘her’:

‘If we help an educated man’s daughter to go to Cambridge are we not forcing her to think not about education but about war? — not how she can learn, but how she can fight in order that she might win the same advantages as her brothers?’ Virginia Woolf

So, why the use of ‘his’ in the first quote?

In the light of the obvious neglect of women as writers, with minds and producers of works in the first quote, it is odd that the first publication I can find dealing with the issue of sexist language is Words and Women, published in 1976 by Anchor Press, MA. Casey Miller (1919 -1997) and Kate Swift (1923 – 2011) wrote this after what they refer to ‘as a simple copyediting assignment’ [1]

In this assignment, they recognised the problems arising from the use of male pronouns, purportedly recognising both genders, but profoundly disadvantaging the girls – the handbook was for a junior high school sex education manual. With their new interest in sexist language, Casey and Swift found an earlier commentary [2]on sexist language in After Nora Slammed the Door (World Publishing Company, 1964) by Eve Merriman. A chapter was dedicated to ‘Sex and Semantics’. [3]

In this assignment, they recognised the problems arising from the use of male pronouns, purportedly recognising both genders, but profoundly disadvantaging the girls – the handbook was for a junior high school sex education manual. With their new interest in sexist language, Casey and Swift found an earlier commentary [2]on sexist language in After Nora Slammed the Door (World Publishing Company, 1964) by Eve Merriman. A chapter was dedicated to ‘Sex and Semantics’. [3]

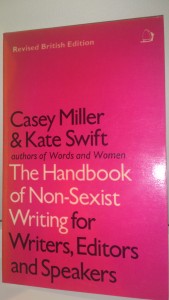

After Words and Women was published, and newly sensitized to the language they heard every day [4]Casey and Swift wrote The Handbook of Non-Sexist Writing for Writers, Editors and Speakers (1979) published by Harper and Row, NY. A second edition was published in 1980. The original provided a myriad of American examples of sexist language. But, of course, the Americans were not alone. Stephanie Dowrick provided numerous British examples in the Revised British Edition and published by The Women’s Press.

The first paragraph of their introduction sums up their reason for the book, and the problems faced by those who want to make language gender neutral:

For whatever reasons – goodwill, a sense of justice, an editor’s instructions, the pursuit of clarity – a growing number of writers and speakers are trying to free their language from unconscious semantic bias. This book is intended for them. It will probably be of no use to people who, for an equal number of complex reasons, actively oppose linguistic change or fail to detect the messages of prejudice others hear.[5]

[1] Elizabeth Isele, Interview ‘Casey Miller and Kate Swift: Women Who Dared Disturb The Lexion’, Willa, fall 1994.

[2] Better researchers than I am? Or a warning not to let information disappear because it ages?

[3] Isele.

[4] Isele.

[5] Casey Miller & Kate Swift The Handbook of Non-Sexist Writing for Writers, Editors and Speakers, (1980) The Women’s Press, UK, p.2.