On Easter Sunday 27 March 1921, two young women from County Cork, Margaret Crowley and Margaret O’Neill, set out on a bicycle journey across the county to deliver an important message to their Irish Republican Army (IRA) comrades who were planning an attack on a nearby police station. Despite travelling twenty-five miles from Kilbrittain to Rosscarbery through areas subject to the increased scrutiny of martial law, they avoided catching the attention of patrolling soldiers and police. Having received the dispatch, an IRA officer ordered the women to stop in several villages on their return to Kilbrittain to place wreaths on the graves of fallen IRA men. This circuitous route – combined with curfew and travel restrictions and unseasonable snowfall – made the mission arduous and dangerous, taking O’Neill and Crowley two days to complete.[1] Though the content of the message is unknown, it was presumably valuable information, as the attack on the Rosscarbery barracks was a success.

These women were part of the republican organization, Cumann na mBan (‘The Irishwomen’s Council’), that played a crucial role in the movement for Irish independence and the guerrilla conflict that emerged from it, the Anglo-Irish War (1919-1921). However, the contributions of women like Crowley and O’Neill to this movement have been overwhelmingly obscured in the historiography of the Irish Revolution (1913-1923), which continues to be driven primarily by the voices and experiences of men. However, since the 1980s, historians have been working diligently to situate women within the narrative of the revolution, using new methodologies and sources to emphasize women’s pivotal contributions to Ireland’s coincident nationalist and feminist movements.[2]

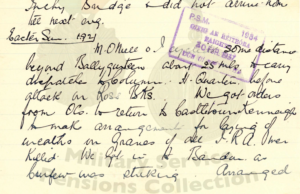

To this end, few resources have been as valuable as the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC), which – since 2014 – is being made available in batches online. Among the collection’s more than 300,000 individual files are the applications of revolutionaries for pensions under Ireland’s Military Service Pensions Acts of 1924 and 1934. These acts required applicants to recount specifics of their involvement in the revolution. Containing the records of more than 75,000 men and women, the MSPC is ‘the most detailed archive available for charting the activities of women in the Irish revolution’.[3] Without the MSPC, republicans like Margaret O’Neill and Margaret Crowley would be virtually impossible to trace and study.

Having used the collection to uncover the forgotten story of a small group of republican activists in rural Ireland on the eve of the revolution, I know the value of MSPC as a tool for recovery.[4] However, I wanted to do more than just emphasize the extent and nature of republican women’s activism; I wanted to understand how that activism (and women’s experience of it) was gendered. So I identified a small, rural cell of fourteen Cumann na mBan women from Kilbrittain County Cork to find out how sex shaped the experience of ‘ordinary’ (if such a word can be used to describe revolutionaries) women in the Irish Revolution.

I then approached the MSPC microhistorically, scouring the files of these fourteen women to reconstruct the historical moment they inhabited. Contextualizing their activism and participation in the republican movement in this way, I could better understand how their experience was shaped by their sex. While what I uncovered in many ways supported existing research about women in the revolutionary period, it also unearthed nuance – particularly when it came to gender dynamics – that complicates this scholarship.

Reading the files of these fourteen women, I expected to discover that traditional gender norms determined some division of labour in republican organizations: it was Cumann na mBan’s job to provide food and shelter for fugitive IRA men. I also knew it was primarily women who operated the republican movement’s intricate logistics network – they were the ones who hid and transported valuable and highly-illegal weapons and information. However, I did not expect this delegation of responsibility to be as pragmatic as the evidence suggested. Margaret O’Neill and Margaret Crowley were selected as dispatch-runners because their sex afforded them privileges men in martial-law Cork did not have. Women were almost universally perceived as non-combatants, meaning that especially in ‘the initial stages of the war, women were less likely to come under suspicion from the police or to be searched’.[5] They were chosen because they were the best candidates for the job.

Somewhat similarly, my investigation demonstrated that end of life rituals – retrieving, honoring, and burying dead IRA men – quickly became the responsibility of republican women as the conflict escalated in Cork. While women’s relative freedom of movement was certainly relevant, this too seems to have been almost completely pragmatic. As violence increased and more republican men found themselves ‘on the run’, in prison, or dead, it was mostly women who organized and attended funerals. In other words, Margaret O’Neill and Margaret Crowley visited IRA graves because – in the words of one Kilbrittain woman – ‘there was not a man to do it in the place’.[6]

Clearly, division of labour in the republican movement was gendered. While existing literature on women in the revolutionary period supports this generally, microscopically examining a small group of republican women illuminates the enormous complexity of this phenomenon. Getting to ‘know’ these women through the MSPC – their relationships, their world, and their politics – it became easier to identify where and how much their sex shaped their experience. Margaret O’Neill and Margaret Crowley’s assignments in March 1921 were gendered, but in different ways. They were made couriers because their sex made them best suited for the job; they travelled to burial sites because there were few men who could make the trip.

This is why I find the MSPC so valuable. Its immense detail makes it an excellent tool for those looking to understand the nuances of complicated phenomena, particularly those that pertain to histories and experiences that have been obscured. Going forward, the possibilities seem endless; and I am eager to see how historians (particularly those of women during the revolutionary period) harness the collection to change our understandings of early-twentieth-century Ireland.

Image credit: MSPC (or Military Service Pensions Collection), MSP34REF19213: Margaret Manning, p. 22. This image and many more can be found on the MSPC search site.

Andrew Himmelberg is a historian of twentieth-century Ireland, focusing particularly on people, communities, and events whose narratives have been obscured in the historiography of the Irish Revolution (1913-1923). His first article, ‘Unearthing Easter in Laois: Provincializing the 1916 Easter Rising’, harnessed Ireland’s Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) to uncover and analyze the actions of a small, rural group of republican men in the early days of the revolution. Most recently, his work is interested in republican women, using the MSPC microhistorically to better understand the complexity of women’s experience during Ireland’s revolutionary period.

[1] MSPC, MSP34REF19213: Margaret Manning, pp. 22-3; MSPC, MSP34REF26330: Margaret O’Meara, pp. 17, 24-5.

[2] The first of these key works was Margaret Ward’s Unmanageable Revolutionaries. Since then, excellent additions include: Maryann Gialanella Valiulis and Mary O’Dowd (eds.), Women & Irish History: Essays in Honour of Margaret MacCurtain (Dublin, 1997); Louise Ryan and Margaret Ward (eds.), Irish Women and Nationalism: Soldiers, New Women and Wicked Hags (Dublin, 2004); Senia Pašeta, Irish Nationalist Women, 1900- 1918 (Cambridge, 2013); Linda Connolly (ed.), Women and the Irish Revolution (Kildare, 2020).

[3] Marie Coleman, ‘Compensating Irish Female Revolutionaries, 1916-1923’, Women’s History Review 26/6 (2017), pp. 915-918.

[4] Andrew Himmelberg, ‘Unearthing Easter in Laois: Provincializing the 1916 Easter Rising’, New Hibernia Review 23/2 (2019).

[5] Marie Coleman, ‘Cumann na mBan in the War of Independence’, in John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil, Mike Murphy, and John Borgonovo (eds), Atlas of the Irish Revolution (New York, 2017), p. 400.

[6] MSPC, MSP34REF29236: Mary Walsh, p. 34.

[1] MSPC, MSP34REF19213: Margaret Manning, pp. 22-3; MSPC, MSP34REF26330: Margaret O’Meara, pp. 17, 24-5.

[2] The first of these key works was Margaret Ward’s Unmanageable Revolutionaries. Since then, excellent additions include: Maryann Gialanella Valiulis and Mary O’Dowd (eds.), Women & Irish History: Essays in Honour of Margaret MacCurtain (Dublin, 1997); Louise Ryan and Margaret Ward (eds.), Irish Women and Nationalism: Soldiers, New Women and Wicked Hags (Dublin, 2004); Senia Pašeta, Irish Nationalist Women, 1900- 1918 (Cambridge, 2013); Linda Connolly (ed.), Women and the Irish Revolution (Kildare, 2020).

[3] Marie Coleman, ‘Compensating Irish Female Revolutionaries, 1916-1923’, Women’s History Review 26/6 (2017), pp. 915-918.

[4] Andrew Himmelberg, ‘Unearthing Easter in Laois: Provincializing the 1916 Easter Rising’, New Hibernia Review 23/2 (2019).

[5] Marie Coleman, ‘Cumann na mBan in the War of Independence’, in John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil, Mike Murphy, and John Borgonovo (eds), Atlas of the Irish Revolution (New York, 2017), p. 400.

[6] MSPC, MSP34REF29236: Mary Walsh, p. 34.