Towards the end of my teaching career I knew I had become part of History. Not surprisingly I had to halt videos of the Poll Tax Demonstrations to give an eyewitness account that varied from Andrew Marr’s narrative. However it was the textbook view of the 1970s as an era of terrible industrial relations and decline that troubled me more. The experience of working women, apart from the noble struggle of the Grunwick dispute, seem to have been written out. Women like my mum who was one of the growing majority of British married women who worked part-time or full-time outside the home.[1] Women who often did not have a fridge in 1970 and certainly not a freezer. Who were paid weekly and often shopped daily. Their experiences of inflation seemed to have overlooked by the lively bestselling accounts of Dominic Sandbrook, Alwyn Turner and Andy Beckett. “Going to the shops” was something many contemporary historians had not experienced as part of the pattern of their everyday lives.

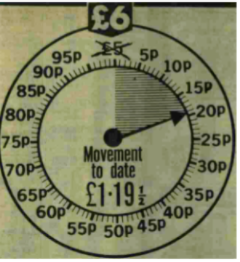

Nor was the influence of the Daily Mirror Shopping Clock’s record of inflation was mentioned. For most of the 1970s, Europe’s most popular newspaper educated its readers about inflation. In 1970 researchers found that the majority of the population still associated the word primarily with pumping up a bicycle and 37% confessed they did not know what it meant at all.[2] The Shopping Clock began with the simple question “How long will a fiver buy this food shopping list?” The list included 33 items, enough to make five family meals and many other essentials including 4lbs of sugar, a packet of tea and a large tin of baked beans. If the Mirror’s “Shopping Clock” had stuck in my mind reading my dad’s discarded paper what had it meant to other readers?

This popular feature ran for over seven years. It appeared every Saturday. Its content was the main front page story twenty two times and it was mentioned on another forty occasions on the front page. It was written overwhelmingly by female journalists – Sally Moore, Joan Smith, Mary Griffiths and Penny Burton – on a paper which employed very few female journalists. The experience of food price inflation appears central to its working-class readers, 45% of whom were women.

In May 1971, 3,250 women strikers in the Plessey factories in Essex used the clock in their wage dispute. On the front page story THE SHOPPING CLOCK STRIKE their shop steward is quoted “Every worker buys the Mirror. Every housewife studies the Shopping Clock to see what’s happening to prices. Everyone can understand it and we know you’re telling the truth.” Kathleen Kelly, the shop steward, and other shop stewards used their copies of the Shopping Clock to negotiate with management when they rejected a 9% pay offer which would last until June 1972. “Negotiators armed with cuttings of the Shopping Clock argued that with prices rising so fast they could not agree to the clause.” “The management don’t read the likes of the Daily Mirror and haven’t heard of the Shopping Clock – so we took along cuttings to show them…they don’t accept what the papers say”. This report is very different from industrial dispute narratives that dominate other accounts of the 1970’s.

The politicians of the period increasingly took notice. Harold Wilson mentioned it in several major speeches[3] and Jim Prior the Agriculture Minister attacked its reliability. Even Edward Heath was forced to demand a “Wages Clock” to show wages were going up even faster. Ministers often blamed husbands for not passing on their wage rises to their wives.[4]

The Shopping Clock page, however, is not just an account of inflation in the 1970s. It gives an insight into the changing world of the food consumer. The £5 basket of thirty three items journalists put together in November 1970 more than doubled to £10.96 by May 1976. But when the basket was restarted in June 1976, the £15 shop includes more fresh food and frozen food and it is all bought in a supermarket.

The Shopping Clock world and its reporters also showed very different attitudes to “housewives”. At the beginning of the decade many reporters were firmly wedded to the notion of bargain hunting individual shoppers who could bring prices down by shopping around. They compared the prices of pet food, pre-packed tomatoes and cheese brands and spreads, ice cream, baby foods, LPs and cups of tea in cafés in the style of the Consumer Association. Harold Wilson and other politicians began to challenge this individualist solution, acknowledging that women did not have the time or the resources to “shop around”. “Easy advice. What about working wives? What about wives with young children? What about wives in area such as villages or underserved estates with only one shop?”[5] The Mirror’s readers certainly agreed in their letters questioning the practicality of shopping around “in small villages where there is only one shop” or “for the old, infirm and disabled? And mothers who have to lug several children around.”[6]

At the beginning of the 1970s the everyday foods of most British families were surprisingly similar but by end of the decade the gap had widened. British women who worked outside the home were often providing the essentials that kept their families out of that “left behind” group who could only afford basic foods[7]. Supermarkets developed essential food labels for these shoppers in the 1990s and 2000s. At the same time the British public accepted foodbanks as part of everyday life. After decades of low inflation shopping has returned to the weekly rising prices of the Shopping Clock era. Some supermarkets have already dropped their basic food ranges,[8] and recently Jack Monroe has drawn attention to the way basic food prices are rising faster than the official rate of inflation.[9] As I plough on with my research it seems to be getting more relevant every day and I wonder how long it will be before the Shopping Clock returns.

[1] Reference to 52.7% 1971 – 56.6% 1980 Women employed 16-64 Labour Force Survey

[2] Behrend H “Research into Public Attitudes and the Attitudes of the Public to Inflation” Managerial and Decision Economics II (1981), 1-8 as cited by Paul Mosely British Journal of Political Science, Vol 14, No 1 (Jan. 1984) p.123 “Popularity Functions and the Role of the Media: A Pilot Study of the Popular Press”

[3] Leader’s speech March 1971, Post Office Engineering Conference in Blackpool June 1971, November 1971 Brighton Conference, April 1972, July 1972, January 1973 and Commons Debate July 1973

[4] Hansard 26 June Vol 839 Food Prices Debate 1017-1018 and Daily Mirror 22 September 1973, p.3

[5] ‘That this House has not confidence in the ability of Her Majesty’s Government to control the rising price of food …. and the cost of other essentials, to maintain the value of the pound at home or abroad, and to create a fair and just society’ Hansard 18 July 1973 Column 499

[6] Daily Mirror, 20 October, p.6

[7] Shinobu Majima, ‘Affluence and the Dynamics of Spending in Britain, 1961-2004’, Contemporary British History, vol. 22/4 December 2008 p.573-97

[8] The Tesco Value brand 1993, Sainsbury’s Essentials, Essential Waitrose in 2009 and Simply M&S 2012 but Sainsbury wound down its Essentials brand in 2019 and the future of these brands looks unclear in a time of high inflation

[9] Jack Monroe, ‘We’re pricing the poor out food in the UK – that’s why I’m launching my own price index’, Guardian 22 January 2022