Increasing socio-economic diversity in the professional services sectors is currently a hot topic. In November 2020, a City of London socio-economic diversity taskforce was launched and last year two of the Big Four accountancy firms published firm-wide socioeconomic pay gaps, with one setting a socio-economic background representation target. By tracing the career path of the accountant Helen Cox née Clegg (1860-1930) we can see how a woman from a low-income family was able to build a professional career in Victorian Britain.

Helen was born in Clerkenwell, the eldest child of at least ten born to George, a master plumber, and his wife, also called Helen. At around the same time Helen left school, aged 15, the business of some family friends failed due to an ‘inattention to accounts’ and this triggered her interest in book-keeping, which she saw as a route to financial independence.[i]

By 1875 there were a number of low-cost adult education options open to women who were prepared to do a double shift and study while working. Helen started with evening classes in book-keeping at the College for Working Women, where class sizes varied between 18 and 26 women. She went on to study at the College for Men and Women at Queen’s Square and Birkbeck College and finally took her accounting exams through the Royal Society of Arts.[ii]

With the theoretical part done, Helen had to get relevant work experience and was helped by an un-named man who let her shadow him. On one occasion he took Helen to a shop to examine their books. ‘The youths sitting on their high stools in the counting-house were overcome with laughter on seeing a woman among them.’ Helen was undeterred.[iii]

When it came to getting paid work, it was women who stepped up. Helen’s first paid job came through Louisa Goold, a former principal of the Working Women’s College and later principal of Morley College. She and Helen were members of the same amateur theatrical society and, discovering Helen’s training, Louisa asked her to look over the society’s accounts. Helen’s next break came courtesy of Henrietta Müller, tax protestor and newspaper owner, who employed Helen as the auditor for the Women’s Penny Paper. Henrietta was a friend of Frances Lord, whose sister, Emily was running a school in Notting Hill and went on to found the Norland Institute. Helen took on that auditing job, too, giving her a vital foothold in the education sector.[iv]

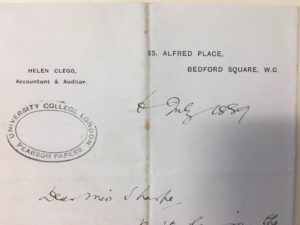

By 1887, Helen was running her business from the family home at 25, Alfred Place near Bedford Square. Probably through Henrietta Müller, she was introduced to Karl Pearson’s radical Men’s and Women’s Club. She only went to one meeting but exchanged a number of letters with Maria Sharpe, the Club’s Secretary. In the summer of 1889, she shared her excitement at being asked by Beatrice Headlam, estranged wife of the Christian Socialist vicar Stewart Headlam, to go to Lincolnshire and audit the Massingberd Arms. Under the ownership of Emily Massingberd, this pub was now a temperance hotel. ‘It will be a new experience: fancy counting the boxes of cigars + the fruit drinks + mineral waters?’ Helen wrote.[v] Emily and Beatrice would go on to found the influential Pioneer Club in 1892.

Conducting a professional business from home brought challenges and in the end Helen’s family agreed to re-organise their living space to give her an office. ‘I think it is likely that more work will come to me when I have a corner of my own,’ Helen wrote. ‘This room to myself may seem a small thing – but it is very serious to me – for I feel that I have the power to command more work + to help to open another career if only I could be freer than I have been. My sisters are very kind + helping me in planning small economies for my furnishing.’[vi] Two months later Helen had a new letterhead.

Helen’s new letterhead, July 1889: Courtesy of Pearson Collection, UCL Archives

On 25th August 1890, aged 30, Helen married Harold Cox, a barrister, economist and member of the Fabian Society.[vii] They set up home at 1 Kings Bench Walk in Temple. Helen’s mantra was that conscientious work was a woman’s best recommendation. Word of mouth spread about her services, particularly in the education sector, and her client base quickly expanded to include a number of girls’ schools in London and further afield. ‘Imagine what it would mean to acquaint yourself, say, with the precise number of pupils who take milk for lunch, and you will have some idea of the mastery of detail required by a competent accountant,’ she said.[viii] Helen was also passionate about equipping women to manage their own money. She created an Investment Record Book, published by Eden, Fisher and Co, so women could keep track of the purchase price of stock and record whether it had shown a gain or a loss.[ix]

In the 1906 General Election, Harold Cox campaigned for the Liberal Party and was elected M.P. for Preston, a seat he held for four years. Helen took on at least some of the expected responsibilities of an M.P.’s wife, hosting receptions and giving out prizes, but her business kept her very busy.

When the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 was passed and women were finally allowed to apply to be chartered accountants, Helen was 59. Although she carried on working for several years, she did not become a member of any official accountancy body. Without a notable accountancy ‘first’ on her CV, her death in 1930 went without comment and she disappeared from the annals of the accountancy profession but now, nearly a century later, her achievements deserve more recognition.

Lizzie Broadbent is the founder of ‘Women Who Meant Business’, celebrating women born in the reign of Queen Victoria who were involved in a wide range of commercial enterprises.

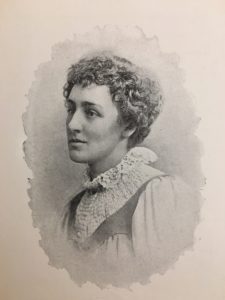

Image of Helen Cox reprinted with kind permission of Cambridge University Press.

[i] ‘Professional Women Upon Their Professions No.22 Accountant and Auditor. Mrs Harold Cox’ in The Queen 29th September 1894 by Margaret Bateman

[ii] Ibid

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Ibid

[v] Karl Pearson Papers 1/6/9 – Letters from Helen Clegg to Maria Sharpe; UCL Special Collections

[vi] Ibid

[vii] The Morning Post 28/8/1890

[viii] ‘Professional Women Upon Their Professions No.22 Accountant and Auditor. Mrs Harold Cox’ in The Queen 29th September 1894 by Margaret Bateman

[ix] Ibid