I’d been in the Women’s Library at LSE for hours, going through oral history transcripts in the Women Against Pit Closures collection. I’m not being hyperbolic when I say I felt close to tears. These women’s lives had been transformed. And all because of a few sandwiches.

While middle class feminists were consciousness raising at Oxford University, the miners’ wives were doing it in the kitchens of welfare halls. Cooking soups and stews, creating food parcels, and cutting sandwiches. It doesn’t sound much, but one reason the 1984/85 miners’ strike lasted so long was because these women kept families fed.

The strike transformed the women’s lives too. Some moved on to the picket lines and marches in London. Others remained on the food front. Regardless of their contribution, the impact was the same. The interviews were littered with comments like, “I’d never done much with my life before” and “I was just a bored housewife”.[I] Following the strike, many returned to education, and a few embarked on political careers.

While being in the kitchen has been derided in the past, by exploring the different ways women have used food, we can reframe it as a powerful political tool. Because looking back over the generations there’s a clear pattern: our political leaders repeatedly make mistakes that leave this nation hungry, then ordinary women go in and fix things.

Back in time

This pattern of female resistance dates back to at least 1629. Bad harvests, economic depression, and Charles I selling licences to export British grain, left the hungry people of Maldon feeling powerless, as they watched ships loaded with food sail across the English Channel. Housewife, Ann Carter, later known as Captain Ann, decided enough was enough. She led a rebellion of 300 villagers to the wharf. They ransacked the warehouses, held ships ransom and stole four tonnes of grain. She was later tried, found guilty, and hanged along with three others for her role in the rebellion.[ii]

In 1795, in similar economic circumstances, a group of women in Manchester took direct action against escalating food prices. Seizing carts carrying food, they sold the produce to onlookers for what they felt was a fair price, returning the takings to the driver. The movement soon spread through the country. These rebellions were predominantly led by women due to their position in the home as the purchasers and providers of food. It became known as the Revolt of the Housewives.[iii]

Scope of resistance

Not only did this pattern of women using food as a political tool go back further than I anticipated, it was far richer. There were the wet nurses at the Foundling Hospital in London, who were arguably our first foster carers. In the days before infant formula, they saved the lives of thousands of abandoned babies. Meanwhile, in 1914, Sylvia Pankhurst campaigned for free milk for children in the East End. In the face of escalating food prices, she argued that the state should take control of the production and distribution of food, to prevent children going hungry.[iv]

During WW2, all women queued, rationed or grew their own food to ensure their families were fed. Others, like Nella Last, went one step further, volunteering with the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) to keep troops on the home front fed. Labour MP, Ellen Wilkinson, funded canteens in safe zones for German trade unionists resisting the Nazis. These canteens were vital, as it was often when the anti-fascists came out of hiding to find provisions that they would be caught and shot.

For those who’ve made Britain their adopted home, food provides a sense of community and belonging. When Jews came to the East End from the end of the 19th century, the establishment of Kosher cafes, luncheon clubs and Kosher food in hospitals, provided a sense of safety and connection. When the Bengalis arrived in the 1970s, the women of the Jagonari Centre used food in a similar way for their community. In the 1920s, Amy Ashwood Garvey, a Jamaican pan-African activist, established the first Caribbean restaurant in the West End, providing her people with a taste of home. It also served as a centre for political meetings.

During the 1980s, Britain saw huge advancement in scientific understanding around nutrition, with an increased appreciation that food could be medicine. Inspired by these principals, professional chef, Amanda Falkson, co-founded Food Chain, providing regular hot meals for people living with HIV and AIDS. It’s impossible to say whether lives were saved, or even prolonged, but it’s undeniable the service provided connection and community during an era defined by fear and heartbreak.

Today, women continue to use food as a political tool. I’m developing an oral history collection with women who’ve set up food banks and cooperatives, or who cook for climate activists going through the judicial system. Then there’s the women survivors of the Grenfell fire disaster, who set up a community kitchen. Initially a practical resource for those left homeless, it’s become a shared space to talk, laugh, cry and heal. As one women said: “Food is love. Simple as that.”[v]

While many women wouldn’t called what they were doing resistance – especially those simply fighting to put food on the family table – arguably it was. They were resisting poverty, hunger and starvation, often while the elites flourished. As the Afrocentric British historian, Stella Dadzie says, sometimes simple survival is an act of resistance.[vi]

For further updates on Kitchen Resistance, and other hidden histories, subscribe to Esther’s Substack newsletter – Missing From History

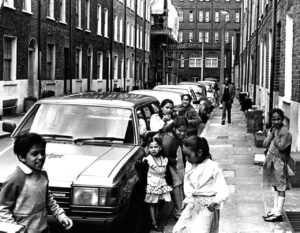

Top image credit: Support the Miners March, Wikimedia Commons

Esther Freeman is a social historian, writer, and activist. With a passion for uncovering untold stories, she’s spent 15 years researching the history of women activists. Since 2020, she’s hosted Rebel Women, a podcast celebrating radical women past and present. She runs the Substack newsletter – Missing from History. She lives in East London with her daughter and their mischievous dog, Mac.

[i] Interviews with women involved in the miners’ strike 1984-1985, Women’s Library, ref: 7BEH/1/1

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ann_Carter_(rioter), accessed 28th October 2025

[iii] https://tribunemag.co.uk/2025/02/the-revolt-of-the-housewives/, accessed 28th October 2025

[iv] Women’s Dreadnought, 19th January 1918

[v] Oral history interview with Amanda Falkson as part of Share UK’s Kitchen Resistance project, 29th July 2025

[vi] Stella Dadzie interview on History Extra podcast about her book, A Kick in the Belly: Women, Slavery and Resistance, 21st October 2020