The human brain takes as little as 13 milliseconds to process an image that flashes in front of our eyes. By comparison, we generally spend very little brain power thinking about the formation and curation of the images which surround us and shape our culture. But should we be thinking more critically about what makes up our visual world?

We are so used to seeing the feminine figures of the Virgin Mary and Venus on the walls of our art galleries and in the culture around us that we might think that women are well represented in our visual culture. In fact, it is only certain women, created by certain artists who dominate Western visual culture, and officially no professional female artist existed in Britain before 1936. The social powers that prioritised white, educated, male voices ensured that queer people, working class people, and women were excluded formally and informally from shaping the culture in which they lived. When we have surviving works by female artists, they are often restricted to “suitable” topics of women in the home. Studies of still life floral arrangements and pastoral landscapes were just about tolerated, being considered genteel enough to not give women any ideas above their station.

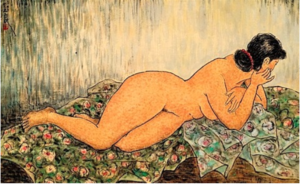

Pan Yuliang’s (1897–1973) paintings are anything but genteel. From being sold to a brothel by her uncle and marrying a client as his second wife, Pan spent her life subverting expectations. Her artistic training came from revolutionaries who were determined to “modernise” China’s culture by adopting European theories and forms. Pan encapsulates the conflicts between femininity, feminism, modernity, and tradition in her art. But her art has rarely been the focus of analysis, overlooked in favour of her dramatic life.

I was determined to bring Pan Yuliang back to the centre of discussions about her work. More importantly, I wanted to break away from the overwhelmingly white and male practices of art history that would reduce Pan to an imitator, a non-white artist merely “inspired by” the real greats (who happen to be white men). By sitting with Pan’s art and working with what I could see, not what I knew about art history, I met Pan as the revolutionary, innovative, remarkable artist she should be known as.

In the early years of her career, Pan favoured oil painting as a medium. Later, after she was established as an artist of some renown and, importantly, had been exiled from China, she turned to caimo ink-and-watercolour instead. This technique combined the bold fluid lines of Chinese ink drawing with the uniquely European figure of the Nude woman. She produced hundreds of pieces with naked women at home, outdoors, at rest, and at play. And in the hundreds of works, there was not an ounce of shame.

Western art history tells us that the male gaze is central when we look at a woman. Moreover, Western culture reinforces the idea that being a woman is defined as how one is performed and perceived. But when I put Pan’s work at the centre, I found a different truth. Pan’s women are defined not by how a male viewer sees them, but by how they occupy the space they take up. They are mothers breastfeeding in the open air, they are readers reclining on a sofa with a tower of books. They are, quite fundamentally, not bothered by whether they fit the norms of women in art.

Pan Yuliang’s nudes are quietly revolutionary. Forgetting Art History 101 and working with paintings by a non-white, non-male artist at the forefront of my analysis is, I hope, similarly quietly defiant. It is not possible to tweak schools of cultural analysis that are rooted in centuries of patriarchal, Eurocentric thinking so that they can be applied to anything not European. The fact that Pan Yuliang’s art does not fit into a Western analytical paradigm is not because she was an outlier, but rather because our way of analysing things only suits what we create. To make our research, our universities, and our culture less white-washed, we need to rethink how we approach resources and start from what they tell us, not what we want them to say.

Image Credit: Untitled Nude, Pan Yuliang (c.1930), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Beth Price is a historian and researcher based in Edinburgh. She specialises in the history of art and images, with a particular interest in gender constructs and identity. She is the co-founder of Breakdown Education, an education community that champions intersectional, diverse, and accessible knowledge networks.