The Modern Venus Competition

In February 1924, an unusual beauty contest took place in London to promote a new film called The Temple of Venus. The Modern Venus Competition set out to find the British woman whose figure best matched the ideal physical beauty represented by the statue of the Venus de Milo.

Thousands of typists, models, actresses, and shop girls entered the competition, each one sending in a photograph along with details of her measurements (waist, neck, wrist, bust, and so on). 150 finalists were selected to appear at the West End Cinema on Coventry Street where they were scrutinised by a panel of female judges.

Stella Pierres was the unknown London actress whose dimensions came closest to the Venus de Milo ideal. Pierres’ vivacious and cheerful personality was also praised as she was announced the winner live on stage in the plush auditorium of the West End Cinema.[1] She received a cash prize, and was immediately catapulted into the public eye.

A whirlwind of activity followed. The Modern Venus screen-tested for film parts. She appeared in Beauty Balls. She won lucrative mannequin roles. She popped up in West End variety shows, and she took part in fashion parades and pageants.

Stella Pierres was soon a regular fixture in the newspapers. She shared fashion advice and weight-loss tips (‘never sit still’).[2] Her celebrity status sold a range of products, from shampoo to setting lotion to starch to jelly. And each time Pierres spotted herself in the popular press, she saved the cutting and pasted it into a scrapbook.

The Stella Pierres scrapbook forms part of the London manuscripts collection at Bishopsgate Institute. It provides fascinating insight into an unusual career, but it only covers the period immediately following Pierres’ competition success. How might we find out what the Modern Venus did next? And was it possible to discover her background?

Who Was Agnes Blois?

One brief cutting in the scrapbook made reference to an actress called Agnes Blois. Could this be the real name of the Modern Venus? As family historians know, the outcome of a genealogical research project often hinges on the subject’s name. The more uncommon, the better. We had struck lucky. Census and other public records confirmed that Stella Pierres was the stage name of Agnes Blois.

Blois had adapted this stage name from her father’s middle name. Ernest Pierrepoint Blois grew up in an aristocratic Irish-British family, but abandoned his life of privilege as a young man to pursue a career in theatre. In the 1901 census, he was living a bohemian existence with his actress wife and her son in a South Coast boarding house.

Born in 1903, Agnes Blois spent her early childhood among musicians and performers. By 1911, the family were enjoying a more settled life in suburban south-west London. Ernest Blois was now a marketing agent in the fast-expanding automobile trade.

Another man with a keen interest in cars about this time was the Australian-born Reginald Empson. Empson was a racing driver whose love of speed and danger saw him acquire a pilot’s licence. In middle age, he turned his insider knowledge of motoring into a career. By 1924 Empson was employed by the Daily Sketch to secure lucrative advertising contracts with car dealerships.

It was through the offices of the Daily Sketch that Empson met Agnes Blois. She arrived one day for a photo shoot shortly after her success in the Modern Venus competition. By 1928, Miss Pierres was Mrs Reginald Empson.

From Diet Pills to Damages

Mrs Empson continued to profit from her looks and celebrity after marriage. Sticking with her stage name, she was the star attraction of a new fashion salon at a department store in south-east London. Her famously perfect Venus de Milo proportions were used to sell diet pills on the pages of the Sunday papers, at a time when boyish figures and an athletic appearance were prized in young women.

But gradually, Mrs Empson withdrew from public engagements. By 1937, her star had fallen so far that one tabloid journalist included the case of Stella Pierres in an article warning young girls not to rely on their beauty for worldly success.[3]

Then in 1939, disaster struck. Reginald Empson was the passenger in a car heading through France to attend the Monte Carlo rally when his vehicle was hit by a lorry. Empson was killed outright in the impact. The driver, Kay Petre, survived the collision.

At this time Petre was one of the best-known female rally drivers in the world. The following year Mrs Empson successfully sued Petre for damages. In an age when it was taken for granted that a married woman would be financially supported by her spouse, the payment was to compensate Empson’s widow for the loss of her husband’s income, but the sum awarded wouldn’t support her for long. How could Mrs Empson supplement this amount? What line of work would suit a former model and beauty queen fast approaching middle age?

The Sobbing Miss Venus

At the height of her fame in the mid-1920s, Pierres wrote a candid assessment of the pitfalls of life as an actress and model. The piece concluded: ‘It is a crime to be poor in our profession, or at least to show it.’[4] By 1950, Stella Pierres found it increasingly hard not to show her poverty. Her savings gone, she moved from one rented apartment to another leaving a trail of rent arrears and unpaid bills in her wake.

She became engaged to a wealthy businessman who expected her always to appear well-dressed on their evenings out. She struggled to meet this expectation, pawning old items of jewellery to keep up with the latest fashions. Then, when her fiancé called off their engagement, Pierres took him to court for breach of promise.

The local and national press went to town on this story. Every headline made sensational reference to the plaintiff’s youthful success as a beauty queen, and her reduced circumstances today: ‘former Miss Venus sobs in Witness Box’; ‘Miss Venus Weeps Over Trousseau’; and so on.[5] The coverage was detailed, and quite uncomfortable to read.

A key part of Pierres’ claim was for £400 spent on a trousseau during her engagement, so five suitcases of dresses, coats, and underwear were produced for the jury. An expert witness suggested that some of these items were so old-fashioned they must have been bought before the couple met. Pierres denied this charge between extended bouts of sobbing in the courtroom.

The jury found in favour of the Modern Venus, who was awarded £2,000. Following her 1950s courtroom victory, our subject again vanished from view. As far as we can tell, Stella Pierres did not marry again. Nor did she have children. Instead, she lavished affection on her beloved apricot poodle who at one time had his own representation, even appearing in a West End musical.

Stella Pierres’ death is recorded in 1982. Now known as Agnes Empson, she was living in semi-detached comfort in north-west London. Probate records indicate that she was no longer struggling financially. Perhaps she had invested her money shrewdly. Possibly she’d inherited an amount from her wealthy birth family. Many questions remain, frustratingly, unanswered. Our search for Stella Pierres continues.

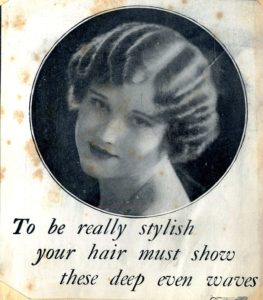

Image of Stella Pierres is courtesy of Bishopsgate Institute.

Dr Michelle Johansen is a social historian specialising in the history of modern London, with a particular emphasis on social class and mobility, gender, professional lives, and regional identities. Her publications include articles in Teaching History, the London Journal, and Cultural and Social History.

Join us for an exploration of the changing experiences of women in modern Britain. This in-person course introduces less well-known subjects, whose lives are documented in the special collections at Bishopsgate Institute. Drawing on original historical sources such as letters, photographs, and scrapbooks, we’ll get to know upwards of twenty ‘forgotten women’ among them campaigners, community workers, pacifists, politicians, sex workers, and secretaries.

https://www.bishopsgate.org.uk/whats-on/activity/forgotten-women-1880s-to-1960s

[1] ‘Film Facts and Fancies,’ The Northern Whig and Belfast Post, 11 March 1924, p.11

[2] ‘Jumping to Conclusions’, undated press cutting in Stella Pierres Scrapbook (1924-25), Bishopsgate Institute and Archive, LCM/326

[3] ‘Is Beauty Worth all the Fuss Made Over It?’, The People, 5 June 1937, p.10

[4] Untitled, undated press cutting in Stella Pierres Scrapbook (1924-25), Bishopsgate Institute and Archive, LCM/326

[5] ‘“Miss Venus” Weeps Over Trousseau’, Daily Mirror, 22 January 1955, p.1; ‘Former Miss Venus Sobs in Witness Box’, Yorkshire Post, 22 January 1955, p.5; see also Birmingham Gazette, 22 January 1955, p.5; The Courier and Advertiser, 28 January 1955, p.5