“you don’t get well […] from forcible feeding, afterwards, ever.”[1]

These words were proclaimed by Maude Kate Smith in January 1975, long after the suffrage movement’s fight for the vote had ended. A militant suffragette, Smith slashed paintings, smashed windows, was imprisoned and forcibly fed after taking part in a hunger strike. However, I had not heard of her until the beginning of 2021 when a lecturer of mine recommended I look at Brian Harrison suffrage interviews.[2] Within these, Harrison interviewed over 180 individuals on the suffrage, politics, and the lives of women in Edwardian period. At random I clicked on interview number 038 which happened to be that of Sybil Morrison.

Morrison was a younger member of the suffrage movement, who became involved in the pacifism movement in 1917. Throughout her discussion with Harrison, she speaks of her partner Dorothy Evans, an organiser within the WSPU, who, like Smith, was also forcibly fed. After listening to her discussion with Harrison, I became completely enthralled with the interviews. I therefore used them as the basis for my entire masters dissertation project: “Making of the Suffragette Self.” It examined how British suffragettes negotiated ideas of selfhood and identity between 1900 and 1920, through the themes of clothing, vegetarianism and hunger striking. The theme of hunger striking interested me in particular.

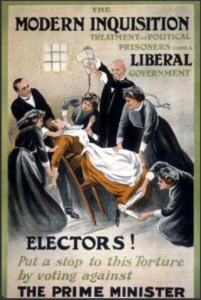

Marion Wallace Dunlop became the first suffragette to hunger strike in July 1909, protesting how her offence was deemed a criminal act, rather than a political one.[3] Many suffrage campaigners followed in her footsteps and took part in political hunger striking between 1909 and 1914. However, such a protest would not have been possible if the narratives surrounding hunger in Britain had not have undergone a period of change during the previous century. In the early 1800s, the hungry poor were seen by many to have bought the hunger upon themselves, through idleness. The middle and upper classes, therefore viewed the hungry as immoral and did little to help them. However, by the end of the century, hunger and starvation began to be viewed as a failure of incompetent governments, neglecting their citizens. Women and children featured heavily in image of hunger from this period, as a means to foster sympathy for the poor and the hungry. The suffragettes politicised this image to increase support for the movement, creating anger at the government who, through their response to the hunger strike, were allowing the continued suffering of women. By doing such they challenged the authority of the government by questioning if their rule is just if it inspires death by hunger for the women.

By September 1909, the government, fearing the implications of releasing the hunger striking prisoners early, introduced the practice of forcible feeding. It was an experience which Maude Kate Smith described as “torture”. She recalled in her interview that the doctor who force fed her,

“got something very, very hard, forced it up my nostrils and injured the […] membrane […]. And he disarranged it so that it always is tender, and it still bleeds now and again. That’s after 60 years!”[4]

She went on to describe how most of the women got chronic colitis after the first two weeks of forcible feeding, regardless of whether they were fed gently or not. In Morrison’s interview, she describes the impact of hunger striking and force feeding similarly. She herself had been instructed by the older members of the movement that she was “not to do anything that could get you into prison, until you were twenty-one.”[5] However, her partner Dorothy Evans was older and took part in the protest. Evans experienced long-term pain from forcible feeding, her throat permanently damaged after having a feeding tube forced down it and her hair turning white because of the trauma. The trauma that Evans and Smith and the other suffrage campaigners who hunger struck and were forcibly fed shaped their relationship with their bodies completely. The women gave over their bodies wholly in the name of suffrage, the cause coming before their own health and wellbeing.

My current project extends upon this theme, focusing upon suffrage, gender, and body politics. Towards the end of her interview, Sybil Morrison speaks with Harrison about the strong anti-doctor feelings within the suffrage movement. Together they agree that this was largely on account of how the women were treated when forcibly fed by the doctors within the prisons. Smith furthers this by proclaiming that:

“I’ll tell you they [doctors] are guilty of all sorts of things that the public don’t know. Ooh the hypocrisy, the lies concerning medicine, simply dreadful.”[6]

For Dorothy Evans, this distrust in doctors culminated in her having “loathed the idea of one’s body not functioning properly by itself,” not wanting to visit hospitals or to have surgery.[7] I find the impact which politics had on the campaigner’s health and body fascinating. A healthy body was important for the suffragettes as it demonstrated the strength of both the individuals and the movement as a whole. Whilst I touched upon this during my master’s dissertation, I want to examine this in much greater depth, examining how suffrage campaigners understood their bodies and health in the period between 1870 and 1930. The interviews shall remain vital, the perspectives oral histories offer being important in understanding the women’s own thoughts and opinions about the body.

In both my previous and current projects, I am not on any grand mission to rescue all these women from obscurity. To do so would be near impossible. However, I do wish to place the voices of these women at the forefront of my work. To comprehend how they understood the world, the suffrage movement and themselves through their own words. In using the stories of Sybil Morrison and Maude Kate Smith, I hope to help others better understand the world of suffrage campaigners through their own words.

Image credit: Poster by ‘A Patriot’, showing a suffragette prisoner being force-fed, 1910. Photo by Museum of London/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Celia Hitchen is a history student, looking to begin her PhD. Her research examines how suffrage campaigners understood their health and bodies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

[1] Interview with Mrs Lyndal Evans, conducted by Brian Harrison, 22nd March 1975, London, LSE Library Collections, 8SUF/B/034. Interview with Miss Sybil Morrison, 8SUF/B/038.

[2] Oral Evidence on the Suffragette and Suffragist Movements: the Brian Harrison interviews, conducted by Brian Harrison, 1974-1981, LSE Library Collections, 8SUF/B.

[3] James Vernon, Hunger: A Modern History (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007), 61.

[4] Interview with Maude Kate Smith, conducted by Brian Harrison, 30th March 1975, Solihull, LSE Library Collections, 8SUF/B/030b.

[5] Interview with Miss Sybil Morrison, conducted by Brian Harrison, 3rd April 1975, London, LSE Library Collections,8SUF/B/038.

[6] Interview with Maude Kate Smith, 8SUF/B/030b.

[7] Interview with Mrs Lyndal Evans, conducted by Brian Harrison, 22nd March 1975, London, LSE Library Collections, 8SUF/B/034.