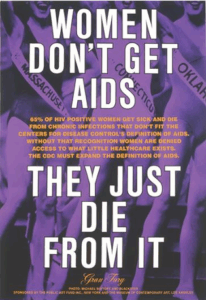

Women Don’t Get Aids They Just Die from It was the headline of an advertisement designed by Gran Fury, which ran in inner city bus stops of Manhattan and in low-income suburban neighbourhoods in Los Angeles in 1991.[i] Gran Fury was an eleven-person, direct-action activist collective formed out of the political activist group, ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). Gran Fury “created works for the public sphere that drew attention to the medical, moral and public issues related to the AIDS crisis”.[ii] Many members of the collective were personally affected by the disease, or knew men and women who were.[iii] In the early nineties, it was difficult for women to gain access to healthcare for their AIDS-related symptoms because the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Americas governing health agency, did not recognise them as susceptible to the disease. Furthermore, at this time, women’s rights were met with institutional backlash, their health needs disastrously ignored and groups like the Women’s Caucus were formed to directly protest the CDC and women’s healthcare rights.[iv] Because of this institutional sexism, Gran Fury designed the poster Women Don’t Get AIDS They Just Die from It to draw public attention to the stated fact, hoping to drive the CDC to revise the definition of HIV and AIDS to include women and their symptoms .[v]

The poster is purposefully provocative in its design, creating “a ghoulish chorus line behind the damming text”[vi]: three women cast in a purple hue, all with their mouths open, smiling, and dressed in swimsuits and heels. The idea behind the execution of the poster was to link “the obsoletion of this image [of femininity] with the obsoletion of the CDC’s definition of AIDS.”[vii] Beneath the text, key information is displayed to both educate women and shame the CDC: “65% of HIV positive women get sick and die from chronic infections that don’t fit the Centers for Disease Control’s definition of AIDS”. In women, the disease commonly manifested as pulmonary tuberculosis, recurrent pneumonia, invasive cervical cancer, immunodeficiency and often severe pelvic pain, and pelvic inflammatory disease.[viii] However, because the CDC refused to acknowledge women’s susceptibility to the disease, or to test women, many women were unaware they could contract it or that their health issues were signs of HIV.[ix] It is believed that in 1991, HIV was the second leading cause of death for black women, and sixth for white women, aged 25-44.[x]

Women were systematically excluded from HIV discourse because of social and institutional sexism. A socially conservative American government, under the leadership of Ronald Regan, “recoiled from a disease publicly associated with gay men – a strong marginalised and stigmatised social group”[xi] and neglected to designate funding to research the disease during the early eighties because of said prejudice. During the early days of the epidemic, when female sex workers in New York failed to show symptoms of the new disease, the gender was written off as potential carriers.[xii] In the late eighties, AIDS had been socially constructed through both scientific discourse and public news as a “threat to civil rights, [an] emblem of sex and death, the ‘gay plague’”. [xiii] The result of the inattention to the highly stigmatised groups meant that the affected communities became politicised, with the face of AIDS activism being the people with AIDS themselves.[xiv] Gran Fury framed AIDS “as a political problem, not just a medical one, and brought about a staggering shift in the American history of medicine as well as in public opinion, while lobbying the federal government to expand its budget for AIDS research”[xv] – executed in direct reference to the CDC and statement of facts on Women Don’t Get AIDS They Just Die from It.

Popular media, in support of the Regan Administration, pushed the discourse that “normal women” did not get HIV – “an assertion that dismissed ever-growing numbers of poor, African American, Latina women with HIV as ‘abnormal’”[xvi], politically pushing both a racist and sexist agenda. The CDC’s refusal to acknowledge the disease, caused a delay in research and healthcare, delays which “were augmented for women, because the very women who were most impacted were least likely to have a voice”. [xvii] In Los Angeles, Gran Fury chose to have half the posters printed in Spanish.[xviii] The decision meant that many more women understood the epidemic, and ultimately protested the institutional racism and sexism these women faced. Arguably, the poster’s exclusion of the very women it was aimed at – black and working-class women – marginalises the women politically and socially, exactly like the CDC and US Government. However, the choice could also be perceived as satirising institutional sexism and marginalisation.

Ultimately, the poster is a critical piece of AIDS activism. The slogan was featured on placards at the Women’s Caucus protest at CDC headquarters in 1990, showcasing the power of the message and exemplifying how the activist group mobilised women across America to also call for change from the CDC. In 1993 the CDC reclassified the definition of HIV and AIDS to include women and their associated symptoms, begin testing and administering treatment to women, all because of burgeoning pressure from the public, thanks to activist groups like Gran Fury, ACT UP and the Women’s Caucus lobbying for change. [xix]

Olivia Gill is a graduate of Art History from the University of St Andrews where she focused on feminist performance art. She is passionate about women’s history and lived experiences. You can often find her with a book or a cup of tea.

Top image credit: Women Don’t Get Aids They Just Die. Advertisement designed by Gran Fury. (Unknown copyright holder).

[i] Public Art Fund. Women Don’t Get AIDS, They Just Die From It. https://www.publicartfund.org/exhibitions/view/women-dont-get-aids-they-just-die-from-it/.

[ii] Gran Fury. “About.” https://www.granfury.org/about.

[iii] The New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts. “Gran Fury Collection, 1987–1995.” https://archives.nypl.org/mss/3648#:~:text=Biographical/historical%20information,Unleash%20Power%2C%20New%20York.

[iv] Face of AIDS Film Archive, “How Feminists Responded to the AIDS Crisis”, 2020. https://faceofaids.ki.se/theme/women-and-aids/how-feminists-responded-to-the-aids-crisis

[v]Alexis Shotwell, “‘Women Don’t Get AIDS, They Just Die From It’: Memory, Classification, and the Campaign to Change the Definition of AIDS,” Hypatia 29, no. 2 (2014): 509–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24542049

[vi] Knight, Christopher, “ART REVIEW: Fury + Political Attack = Graphic AIDS Message,” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1991. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-03-06-ca-91-story.html

[vii] McCartney, cited in Artforum, “Read Their Lips,” 2022. https://www.artforum.com/columns/the-feats-and-failures-of-gran-fury-251734/.

[viii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults.” Recommendations and Reports, 1993. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018871.htm.

[ix] Robert Gober, Bob Gober, and Gran Fury. “Gran Fury.” BOMB, no. 34 (1991): 13.

[x] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Update: Mortality Attributable to HIV Infection Among Persons Aged 25–44 Years — United States, 1991 and 1992.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, July 24, 1993. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00022174.htm

[xi] Tasleem J. Padamsee, “Fighting an Epidemic in Political Context: Thirty-Five Years of HIV/AIDS Policy Making in the United States,” Social History of Medicine 33, no. 3 (2018): 1001–28, https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hky108

[xii] Paula A. Treichler, “Collectivity in Trouble: Writing on HIV/AIDS by Susan Sontag and Sarah Schulman,” Amerikastudien / American Studies 57, no. 2 (2012): 249.

[xiii] Paula A. Treichler, “AIDS, Homophobia, and Biomedical Discourse: An Epidemic of Signification,” October, no. 43 (1987): 35.

[xiv] Mitchell H. Katz, “The Public Health Response to HIV/AIDS: What Have We Learned?” in The AIDS Pandemic, 90–109 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012465271-2/50007-8

[xv] The Metropolitan Museum. “Perspectives: Queer Activist Art.” 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/act-up-gran-fury

[xvi] Tasleem J. Padamsee, “Fighting an Epidemic in Political Context: Thirty-Five Years of HIV/AIDS Policy Making in the United States,” Social History of Medicine 33, no. 3 (2018): 1001–28, https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hky108

[xvii] Durvasula, Ramani. “A history of HIV/AIDS in women: Shifting narrative and a structural call to arms.” Psychology and AIDS Exchange Newsletter 2018 (2018): 30-2023.

[xviii] Gallery 98. Gran Fury, Women Don’t Get AIDS They Just Die From It. Public Art Fund, Card, 1991. https://gallery98.org/2018/public-art-fund-gran-furys-women-dont-get-aids-just-die/.

[xix] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 41, no. RR-17 (1992). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018871.htm ; Yale University Library. n.d. “Why Are Women Invisible in the AIDS Pandemic?” We Are Everywhere: Lesbians in the Archive. https://onlineexhibits.library.yale.edu/s/we-are-everywhere/page/why-are-women-invisible-in-the-aids-pandemic