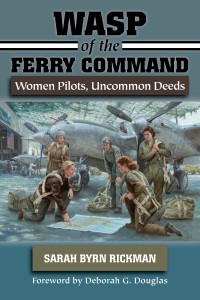

WASP of the Ferry Command: Women Pilots, Uncommon Deeds

Sarah Bryn Rickman

The following story is an excerpt from Sarah Byrn Rickman’s WASP of the Ferry Command: Women Pilots, Uncommon Deeds, out now from University of North Texas Press (March 2016), the story of the women ferry pilots who flew more than nine million miles in 72 different aircraft—115,000 pilot hours—for the Ferrying Division, Air Transport Command, during World War II.

WASP of the Ferry Command is about transitions: transition from civilian life to military life—from having your own room to living in group accommodations with no privacy; moving from 65-horsepower civilian Cub stuff to the 600-horsepower Army advanced trainer, the AT-6, to the mighty 1,695-horsepower P-51; from training, where you’re told what to do, to being given total responsibility for the care and safe delivery of a $45,000 (1944 dollars) aircraft; from being desperately needed to fill the shoes of men headed for combat abroad to being pushed aside by those men when they returned from overseas and wanted your jobs.

Inez Woodward and Jean Landis, both graduates of WASP Class 43-4—the largest class of women recruited (152) and graduated (112)—recounted two of the most memorable stories of their transitions into the life of a ferry pilot.

Jean Landis’ story appears in the next post, 17 March, 2016.

Inez Woodward

“I had orders to pick up a PQ-14 at Wright Field in Dayton and take it to Cherry Point, North Carolina,” Inez related. “It was a one-place airplane [one of the smallest planes the WASP flew].”

“I signed for it, went out, got in, ran it up, and took off.

“Over the Tennessee hills, I watched my oil pressure go down. The nearest Army Field was Lebanon, Tennessee. I landed there. War maneuvers were on and I was in the middle of them. The Red and Blue armies were learning about combat.

“I didn’t want to take off with a defective airplane, so I decided to spend the night in Lebanon. There were no hotel rooms and it was getting along towards dark. ‘Well, I’ll just sleep in the Ready Room,’ I told the officer-in-charge.

“Oh, you can’t do that. There’s too many men around here. You’ll never make it through the night,” he said. He paused, then said, ‘Excuse me a minute.’ A few minutes later he came back. ‘I have a place for you to sleep, but I’m going to take you to dinner first.’

“We had dinner and then he said, ‘Now, you go use the restroom here and do whatever you’re going to do because you’re not going to have a restroom until tomorrow morning when I pick you up.’

“’All right,’ I said, and did what he said. I had no luggage—a toothbrush was about all—because I was flying a one-place airplane.

“So I went with him to this house and we opened the door. There wasn’t a soul in sight. We went up on the landing to a winding staircase. There was a door tucked away. He pushed it open. ‘This is your room. Lock the door. Do not come out until I come and knock on your door tomorrow and give you my name.’

“I said, ‘All right.’

“It was like an oversized closet, but it had a clean bed in it. I was tired after that ordeal. I lay down and went to sleep. But all night long I heard men coming and going up and down the stairs. A couple of drunks even bounced off my door, apparently trying to make it around that corner in the hall. Slowly it dawned on my thick skull where I was. —But I was there, so what about it!

“The next morning, the officer knocked at my door, identified himself, and took me to breakfast. I called Berry Field in Nashville, an Air Transport Command base about thirty miles away, and asked them to let me have a straight-in approach. When I got there, they ripped out the gas lines as well as the oil lines and rebuilt them.

“Oh yes, they entertained me royally while I was at Berry Field.”