When I began researching Hard Work – But Glorious: Stories from the Herefordshire Suffrage Campaign, I was keen to find images of the women I was writing about. Their thoughts and words were important but being a huge fan of old photographs, I really longed for a visual connection. I quickly discovered photos of Florence Canning, Chairman of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage. Constance Radcliffe Cooke, suffragette and social reform campaigner, appears in a wealth of images held at Herefordshire Archives and Records Centre. Beatrice Parlby, a local suffragist, can be seen dressed in her academic cap and gown in a photograph still treasured by her family. Through online searches I found Alice Chapman, a leading Hereford-based anti-suffragist, tending her garden at Carfax House in a publicity photograph for her ‘Home School for the Daughters of Gentlemen’. However, an image of Ethel Mary Davis constantly eluded me, despite her wide-ranging campaigning activities across the West Midlands.

Ethel was the eldest daughter of Louisa and Reverend Thomas Scott: he was the first vicar of Penge, one of the new ever-growing Victorian London suburbs. Ethel married George Davis in 1891, who gave up his career as a solicitor to become an Anglican priest in 1902. George was soon working at St Saviour’s church in Saltley, one of the poorest areas of Birmingham, with Ethel supporting him both in his ministry and bringing up their six children.

Alongside their commitments to socialism and social reform, the cause of women’s suffrage was one which the Davises wholeheartedly embraced. Ethel was an active member of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), organising meetings, fundraising drives and travelling across the West Midlands to speak at events. By the time the family moved to Hereford in early 1911, George was already a popular orator and sharing platforms with many of the leading members of the suffrage movement across the country. He later officiated at Emily Wilding Davison’s funeral service in June 1913 and can be seen in the newsreel footage leaving St George’s Church in Bloomsbury. That same summer he was part of the clergy delegation to 10 Downing Street to protest about the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act.

Ethel evaded the 1911 census, together with Ethel May, 18, the couple’s oldest daughter and Molly, the youngest, aged 2. She then embarked on what to begin with was a one-woman crusade to rouse Herefordshire from its suffrage slumbers. Prior to 1911, the anti-suffrage campaign had been far more active in the county, and the local branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) had only met sporadically since its inception in November 1909. Ethel immediately became Secretary to the Hereford branch of the WSPU but worked closely with the local NUWSS: there seems to have been a spirit of cooperation similar to that experienced in cities such as Liverpool. Ethel’s speeches at suffrage meetings are recorded in the local press, and her efforts at fundraising and newspaper selling appear in Votes for Women and The Suffragette. She spoke often about the need for improvements to living conditions for women as well as the vote; here’s an extract of a speech from an open-air meeting held in Hereford on 30 March 1912: ‘Mrs Davis pointed out that this (women’s franchise) was not a party political question. It was a woman’s question for the betterment of women, and must go on. Those better situated must regard themselves as their sisters’ keepers. They wanted the vote so that they could improve their conditions, the standard of living, and alter some of the terrible injustices which hundreds and thousands of women suffered today.’[1]

The WSPU had a stall at the Hereford May Fair in 1912, and a grainy film taken by the Herefordshire photographer Alfred Watkins briefly shows two women and a young girl viewing something from a fairground ride. I thought it must Ethel and Ethel May with Molly checking out how their display looked from a higher level, decorated with foliage, hawthorn blossom and lilac to represent the green, white and violet colours of the WSPU.

In 1913 Ethel wrote in support of women’s ordination during Ursula Roberts’ national campaign but lamented her lack of time to be more heavily involved in this cause due to domestic duties and her suffrage activities. She was also passionate about women’s rights in relation to the law, and regularly attended the Shirehall Assizes to watch proceedings in sexual abuse cases. Ethel’s exasperation with the legal system boiled over in early February 1915, when she called out to Lord Justice Avory during sentencing at an infanticide trial: ‘I protest as a wife and a mother’ and was summarily ejected from the building.

In April 1915 George and his daughters appeared in a photograph published in the Hereford newspapers for a Blue Cross fundraising event. There was still no sign of Ethel! Two years later, the family moved to St Weonards in south Herefordshire, where George was vicar until 1931. His incumbency was initially marked by disputes with Hensley Henson, Bishop of Hereford between 1918 and 1920, who wrote disparagingly of the Davises in his personal journal:

24 May 1919: ‘He is a Socialist, as a former curate of Jimmie Adderley’s, the vicar of St Saviour’s, might be expected to be: she is a “suffragette”, with a reputation for violence earned in the good old days before the War.’[2]

There is no evidence of Ethel being a violent suffragette, but the references to Birmingham got me thinking about images of events relating to her time there. I went back online and found a postcard with two unnamed women and four children all holding collecting boxes during a 1908 collection for Saltley Distress Fund. This was a local charity which helped workers during strikes and labour disputes, with its headquarters at the Adderley Arms in Saltley. Was one of the women Ethel?

Fast forward to 15 October 2021, when an email arrived from Dr Sue Jones, author of Votes for Women: Cheltenham and the Cotswolds[3]. She’d been to the Museum of London some years ago to see Ada Flatman’s scrapbooks[4], and had recently seen online about my lack of success to find Ethel. I’m incredibly grateful as Sue had solved my dilemma: there was indeed a photograph of the 1912 May Fair, but as the names were on the back, I’d not seen them online during my lockdown research. So there is Ethel, Ada, George, Molly in her perambulator, and a crowd of people surrounding the WSPU stall. I could be satisfied that I had finally found Ethel.

(1097 words)

Clare Wichbold retains a keen interest in history after her early career as an archaeologist. Having thrown in the trowel in 1996 she subsequently turned to grant-making and is currently working as Fundraising Manager at The Courtyard Centre for the Arts in Hereford. A latecomer to suffrage research through the 2018 centenary of the Representation of the People Act, Hard Work – But Glorious: Stories from the Herefordshire Suffrage Campaign is Clare’s first book; her next, a biography of Constance Radcliffe Cooke, one of the Herefordshire suffragettes discovered during her research, is currently in the early stages. (96 words)

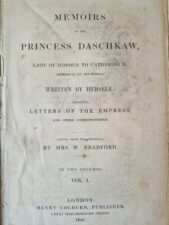

Image 1:Scrapbook compiled by the Suffragette Ada Flatman, (Volume 2). Rights: digital image copyright Museum of London

Image 2: The Cloisters at Hereford Cathedral, home to the Davises between 1911 – 1917, taken in summer 2018 when Three Choirs was taking place in Hereford and Clare was Chairman of the Festival celebrating the Representation of the People Act.

[1] Hereford Mercury, 3 April 1912

[2] The Henson Journals – The journals of Hensley Henson, 1900-1939

[3] Sue Jones, Votes for Women: Cheltenham and the Cotswolds, History Press, 2018

[4] https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/scrapbook-compiled-by-the-suffragette-ada-flatman-vol-2-ada-flatman/1QH9NK87VJeTvw?hl=en